Do you remember how, for a brief moment in human history, you could fix machines by using violence? No university degrees or user manuals required, just a good ole slap o’ the hand to the side or top of the idiot box. And there you go, it works again! This could’ve been caused by a connection error, some faulty wires that didn’t properly transmit the video signal. But the point is you didn’t have to know about that, it used to be a magic solution that sometimes fixed stuff.

We don’t have wires anymore, for the most part. Most of our electronics use a PCB with each component attached to it (usually soldered or screwed). They’re so pervasive and easy to produce you could even use them for garage projects! It’s as easy as printing an image, transfering the ink to the board, applying some chemicals and drilling some holes. And they look waaay better than a mess of cables connecting everything.

While listening to episode 5 (“Charlie Bucket’s dad”) from Daniel Messer’s (@bibrarian) “Cyberpunk Librarian” podcast, I realized our problems are now mostly digital. We’ve figured if we remove the wires we won’t have faulty wires anymore. But that doesn’t mean we fixed the “connection error” problem. In the digital world we could have an API or program failing because we entered the wrong parameters. Or, if we have a long chain of different pieces (which sounds like a generic definition of what a computer or the Internet is), it could be any of those pieces failing.

What this means is most of the times we can’t apply a magic solution and hope for the best. Well, turning it off and on again works sometimes, but it won’t fix all problems. We need to really understand the problem in order to fix it. This is captured very well on Julia Evans’ (@b0rk) debugging adventure games. In these choose-your-own-adventure games you investigate a problem, finding clues like if it were a Phoenix Wright game, until you find out the root cause and fix it. Finding bits of knowledge about a digital problem, that we solve with digital tools.

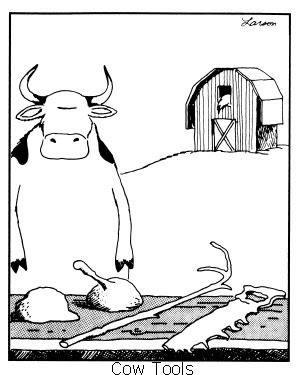

And that’s what concerns this post: tools. Even though “tool” calls up a very physical mental image (like a wrench, hammer or a voltmeter with a display, switch knob and probes), digital problems in digital systems require digital tools to solve. And to use those tools we sometimes need to read documentation, experiment, fix and replace them when they stop working. Just like physical tools!

Daniel’s point about familiarizing yourself with your tools is as valid in software development as it is with librarian tools (or physical tools in a physical job 😛). Yet, perhaps because of the amount of tools or their “locality” (eg. Apple ecosystem used just for Apple development), this is a difficult task. Nevertheless, you would be doing yourself a disservice if you don’t. Learning about your tools is a good way to find ways to make your job easier. You stop depending on others to fix things, you grow your knowledge base, you do a more rewarding job and with your own individual background you could find an obvious solution that isn’t obvious to anybody else. Like in the example at the beginning of the post: by understanding the wires were causing the connection problem, we can ask ourselves: can we fix them? Can we replace them with something cheaper that doens’t have that issue?

That’s all. This post was mostly an excuse to share work by some people I like. I hope you found it useful or interesting in some way. Be sure to check the work done by Daniel Messer (@CyberpunkLibrarian@hackers.town) Julia Evans (@b0rk@jvns.ca), it’s really good! 😄